Should we mandate instruction practices that are known to improve student learning?

This is a summary of a discussion I led through a discussion group. This group is called the “STEM Education & Diversity Discussion Group” and it is organized by students and post-docs at UCSD/Salk Institute/Scripps.

The subject of discussion was about the implementation of well-studied, if not always well-known, educational practices that can facilitate long-term retention of material.

The main source material was a document produced by the Institute of Educational Sciences (IES), called Organizing Instruction and Study to Improve Student Learning.

This document also has some home relevance as Hal Pashler, a UCSD psychologist, spearheaded the efforts of producing this guide. In addition, my personal interest lies close to the interests of the STEM discussion group, but it specifically relates to the translation of research findings from neuroscience and psychology towards education. The document covers some of these findings that have been around for a while (it was written in 2007).

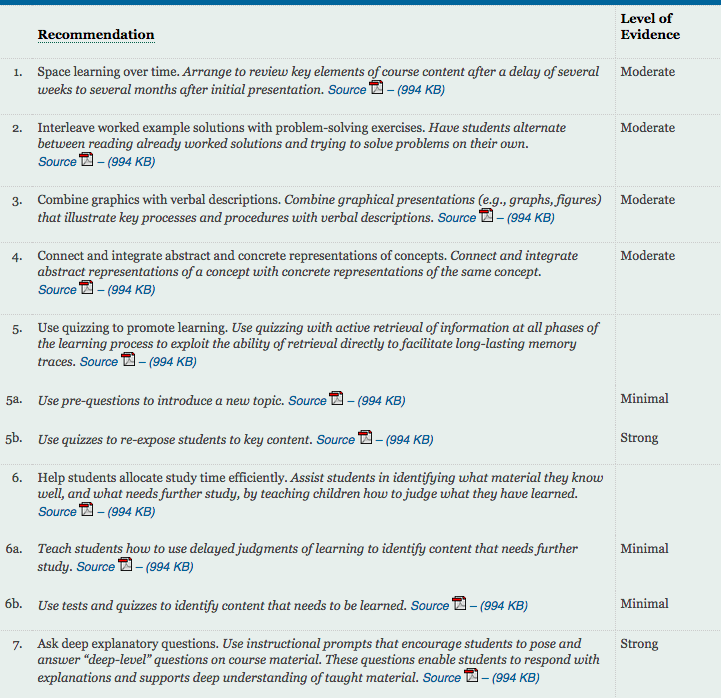

I was interested in discussing some of the concepts discussed in the guide and also generally the thoughts on how it can be implemented. While I won’t go in detail of all of the recommendations in the guide, I included a screen shot here of the list, which again can be reached at the link above.

Recommendations for improving student learning

When I asked the participants in the STEM discussion that day about whether they were aware of some of these concepts, it ranged from “no knowledge” (in the case of spacing effect) to “yes, it’s something I practiced myself”. However, from the small sample size, it was clear that these concepts are not widely-known, despite some of the documentations on how these practices can increase long-term retention of material.

Should teachers be required to practice the recommendations in this document?

I provided this somewhat provocative question because of my belief that if certain practices are known to improve learning, students should be receiving this instruction. I gave the analogy of research and medicine (an analogy which others have made before when discussing education relevance. Note: I learned about this study from taking The College Classroom offered by UCSD’s Center for Teaching Development). In clinical studies, if one group of participants that received a treatment showed overwhelming improvements, it would not just be mandatory for the control group to receive the same treatment, it would be unethical if they didn’t. I believe that there’s no reason why we can’t say the same when it comes to instruction and student learning. If we know that there are practices that are effective in student learning, why shouldn’t it be mandatory that educators implement it?

A counter-argument that others brought up is that there are political realities that an educator must deal with which doesn’t always jive with these kinds of practices. Nevertheless, I think that some of these recommendations are not hard to implement, and that the mindset that the questions that educators should always be asking themselves is “Am I organizing my instruction that is effective for student learning?”