Approaching Bertrand’s box paradox, including with Bayes’ theorem

Bayes’ theorem is one of the most useful applications in statistics. But sometimes it is not always easy to recognize when and how to apply it. I was doing some statistics problems with my Insight cohort when applying conditional probability in one, simpler problem helped me connect it with a slightly harder, baseball-related problem. I’ll talk about the baseball problem in my next post.

Here I’ll talk about how multiple approaches for Bertrand’s box paradox, including with Bayes’ theorem.

# Load packages for coding examples

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

from scipy.stats import binom

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import seaborn as sns

Bertrand’s box paradox

I across this in my old textbook. The problem is famous, but I’m apparently not with the in-crowd because I was not aware of it. It’s called Bertrand’s box paradox.

Problem scenario: A box contains three drawers: one containing two gold coins, one containing two silver coins, and one containing one gold and one silver coin. A drawer is chosen at random, and a coin is randomly selected from that drawer. If the selected coin turns out to be gold, what is the probability that the chosen drawer is the one with two gold coins?

The drawers can be referred to like this:

Box A: G,G

Box B: S,S

Box C: G,S

I’m going to show a few different approaches for the problems. One reason for this is that you can see how the answer can be confirmed. (Again, since this problem is well-known, you might find other explanations helpful, including on the problem’s entry in Wikipedia.) But another reason is to point out some flaws in these other approaches, compared to how application of Bayes’ theorem can be robust.

“Reasoning” approach

One way to approach this is to “reason” your way through the problem. Let’s say that each of the boxes has two drawers. The problem can be re-framed as, “If you randomly choose a box, and then find a gold coin in one of the drawers, what is the probability that the other will be a gold coin?” You can eliminate box B (S,S). Many believe that since the coin must come from either box A or box C, there is a 50% chance that the gold coin must come from box A. However, this is not the correct answer (and also why it’s referred to as a paradox). The right approach would be to consider that the selected gold coin is one of the following three gold coins:

- gold coin 1 from box A

- gold coin 2 from box A

- gold coin 3 from box C

Therefore, it’s a 2/3 probability that it comes from box A. While this approach may help you get an answer quickly, it relies on making the proper assumptions. But the correct suppositions are not always obvious without regular experience doing problems like this. Accordingly, the “reasoning” method must be applied with caution.

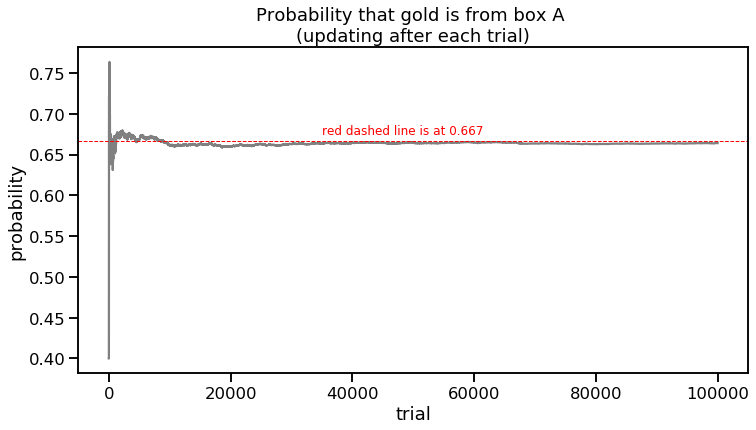

Experimental simulation approach

A second approach can be taking repeated trials through code and seeing where the answer converges. This would be an application of the law of large numbers. Here is some code where I first randomly choose one of the three boxes and then randomly choose one of the two coins in that box. (For box C, which contains a gold and silver coin, I assign drawer 1 as the gold coin and than randomly choose between drawers 1 and 2.)

# Code to run a lot of trials

from collections import Counter

import random

boxes = ["A", "B", "C"]

coin_side = [1, 2] # Assume gold is on drawer 1 of Box C

box_count = Counter()

box_count_wgold = Counter()

prob_A_list = list()

for trial in range(10**5):

# Randomly pick a box

box = random.sample(boxes, 1)[0]

box_count[box] += 1

# Randomly pick coin after picking a box

if box == "A":

box_count_wgold[box] += 1 # we know it will always be gold for box A

elif box == "C":

side = random.sample(coin_side, 1)[0] # assume gold is on drawer 1 of Box B

if side == 1:

box_count_wgold[box] += 1

# Ignore box B (silver, silver box)

# This is calculating the probability after each trial, starting at trial 10

if trial > 10:

prob_A_list.append(box_count_wgold["A"] / (box_count_wgold["A"] + box_count_wgold["C"]))

sns.set_context('talk')

f, ax1 = plt.subplots(figsize=(12,6))

ax1.plot(prob_A_list, color='gray')

ax1.axhline(0.6667, color='r', linestyle='dashed', linewidth=1)

ax1.set_xlabel('trial')

ax1.set_ylabel('probability')

ax1.set_title('Probability that gold is from box A \n(updating after each trial)')

ax1.text(35000, 0.675, 'red dashed line is at 0.667', color='r', fontsize=12);

print("Probability after 100,000 trials: {0:0.4f}".format((box_count_wgold["A"] / (box_count_wgold["A"] + box_count_wgold["C"]))))

Probability after 100,000 trials: 0.6641

One advantage of the simulation approach is that not many assumptions have to be made. One can simply use code to carry out the parameters of the problem repeatedly. However, as you can see, even after 100,000 trials, we don’t get 2/3 exactly. Bayes to the rescue!

Bayesian approach

Let’s remind ourselves how Bayes’ theorem uses conditional probability.

$\text{P}(A|B)$ = $\frac{\text{P}(B|A)\text{P}(A)}{\text{P}(B)}$

Huh? Let’s translate the terms into words.

$\text{P}(A|B)$ = The probability of event A occurring given that B is true. The left side of the equation is what we are trying to find.

The entire right side of the equation is information that we are given (although we have to make sure we put in the right numbers).

$\text{P}(B|A)$ = The probability of event B occurring given that A is true. This is not equivalent to the left side of the equation.

$\text{P}(A)$ = The probability of event A occurring, regardless of conditions.

$\text{P}(B)$ = The probability of event B occurring, regardless of conditions.

Another way of stating the problem is asking “What is the probability that the box chosen is A, given that you have also selected a gold coin?” Substituting the words in to Bayes’ theorem would give us something like this:

$\text{P}(\text{box A} | \text{gold coin}) = \frac{\text{P}(\text{gold coin} | \text{box A})\text{P}(\text{box A})}{\text{P}(\text{gold coin})}$

The entire right side of the equation is information that we are given. The parameters in the numerator are the easiest for which we can plug in numbers.

We know that there is 100% probability of picking a gold coin if we choose box A.

$\text{P}(\text{gold coin} | \text{box A})$ = 1

We are choosing box A randomly out of the 3 boxes.

$\text{P}(\text{box A})$ = 1/3

The denominator ($\text{P}(\text{gold coin}$) might require a closer look. The probability of choosing a gold coin, independent of any other condition, is the sum of the probability of choosing a gold coin in the three boxes.

$\text{P}(\text{gold coin})$ = $\text{P}(\text{gold coin} | \text{box A})$ + $\text{P}(\text{gold coin} | \text{box B})$ + $\text{P}(\text{gold coin} | \text{box C})$

$\text{P}(\text{gold coin})$ = $1 \times \frac{1}{3} + 0 \times \frac{1}{3} + \frac{1}{2} \times \frac{1}{3}$

$\text{P}(\text{gold coin})$ = $\frac{1}{2}$

Therefore,

$\text{P}(\text{box A} | \text{gold coin}) = \frac{1 \times \frac{1}{3}}{\frac{1}{2}} = \frac{2}{3} $

Awesome. This is how we apply Bayesian statistics in this problem. Let’s level up and try a problem that is a little more complicated. See you in the next post!