Bayes-ball part 1: determining a true talent level

In my previous post, we saw how Bayes’ theorem was applied to a relatively simple problem with Bertrand’s box paradox. Here I’ll talk about another application of Bayes’ theorem, which is slightly more complicated but I’ll draw links to the simpler problem. This problem also gives us a chance to take a look at the binomial distribution!

# Load packages for coding examples

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

from scipy.stats import binom

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import seaborn as sns

Problem scenario: Suppose that you are scouting high school baseball players. Imagine that there are only two types of high school hitters, those with a true talent 10% hit rate and those with a true talent 25% hit rate. We also know that 60% of high school hitters are in the 10% hit rate group and the remaining 40% are in the 25% hit rate group. Suppose we have observed a hitter, Bobby Aguila, over 100 plate appearances and he has hit at an 18% rate. What is the probability that Aguila has a true talent level of 10% hit rate?

Bayes’ theorem can be applied here but it may take a little more digging to see it. Let’s create some notations before we get started.

T10 = true talent 10% hit group

T25 = true talent 25% hit group

18H = 18 hits in 100 at-bats

The original question could be phrased as “What is the probability that Aguila has a true talent level of 10% hit rate, given that he has 18 hits in 100 at-bats?”

In Bayes’ theorem, we can therefore structure our equation like this:

$\text{P}(\text{T10} | \text{18H}) = \frac{\text{P}(\text{18H} | \text{T10})\text{P}(\text{T10})}{\text{P}(\text{18H})}$

Connecting with Bertrand’s box paradox

The easiest parameters to plug in is the probability that the hitter, in the absence of any condition (without knowing anything else), is from the T10 group. We were given that explicitly in the problem:

$\text{P}(\text{T10})$ = 0.60

Note that this is analogous to $\text{P}(\text{box A})$ in Bertrand’s box problem. In that problem, we knew the value implicitly ($\frac{1}{3}$) since the drawer was chosen at random.

The other parameters of the baseball question are less obvious to determine, but we can get some clues after translating back to words. Let’s start with $\text{P}(\text{18H})$. This is equivalent to ${\text{P}(\text{gold coin})}$ in Bertrand’s box paradox. In the box problem, we broke this down by summing up the probabilities for a gold coin for each drawer. Here, we would sum up the probabilities of a hitter getting 18 hits in 100 at-bats if he is in the T10 group and in the T25 group.

${\text{P}(\text{18H})}$ = $\text{P}(\text{18H} | \text{T10})$ + $\text{P}(\text{18H} | \text{T25})$

$\text{P}(\text{18H} | \text{T10})$ is asking “What is the probability of getting 18 hits in 100 at-bats, given that they have a true talent level of 10% hit rate?” $\text{P}(\text{18H} | \text{T25})$ is basically the same question but for the T25 group. Here is where we need to recognize that this is an application of the binomial distribution. Let’s digress briefly.

Application of the binomial distribution

This problem fits the binomial assumptions:

- Two outcomes: For each plate appearance, we care that he is getting a hit (1) or no hit (0).

- Constant p: The probability p getting a success has the same value, for each trial. This would be 0.10 for the group that has a 10% hit rate true talent level and 0.25 for the T25 group.

- Independence: This is the one assumption that may be potentially violated since a hitter’s confidence may fluctuate based on recent performance. However, in this situation I think it is okay to assume at-bats are largely independent of each other.

The probability mass function is: $\text{P}(X = k) = \binom n k p^k(1-p)^{n-k}$

where: $\binom n k = \frac{n!}{(n-k)!k!}$ (the binomial coefficient).

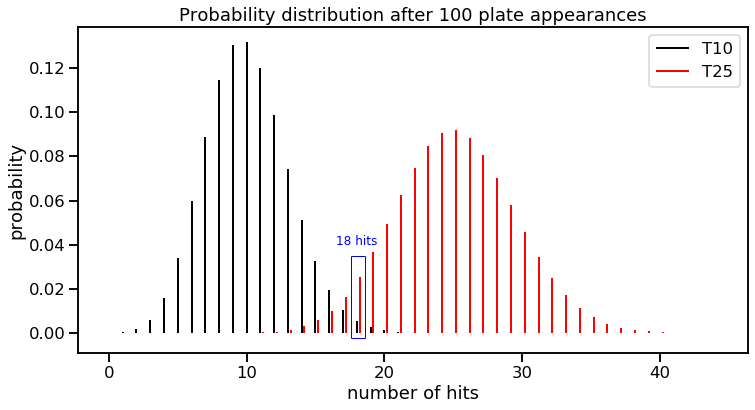

In this problem, k = 18 and n = 100. And as mentioned above, the T10 group has p = 0.10 while T25 has p of 0.25. We can start plugging values in. However, this visual may also help see what is going on.

from scipy.stats import binom

# T10 group

n, p = 100, 0.1

fig, ax = plt.subplots(1, 1, figsize=(12, 6))

rv = binom(n, p)

x = np.arange(0, 45)

ax.vlines(x, 0, rv.pmf(x), colors="k", linestyles="-", lw=2, label="T10")

# T25 group

n25, p25 = 100, 0.25

rv25 = binom(n25, p25)

x25 = np.arange(0, 45)

ax.vlines(x25 + 0.2, 0, rv25.pmf(x25), colors="r", linestyles="-", lw=2, label="T25")

# Formatting

ax.set_ylabel("probability")

ax.set_xlabel("number of hits")

ax.set_title("Probability distribution after 100 plate appearances")

# Box around 18 hits

ax.text(16.5, 0.04, '18 hits', color='b', fontsize=12);

ax.vlines(17.6, -0.0025, 0.035, colors="blue", linestyles="-", lw=1)

ax.vlines(18.6, -0.0025, 0.035, colors="blue", linestyles="-", lw=1)

ax.hlines(0.035, 17.6, 18.6, colors="blue", linestyles="-", lw=1)

ax.hlines(-0.0025, 17.6, 18.6, colors="blue", linestyles="-", lw=1)

ax.legend();

We can see that each true talent level group has its own probability distribution for different hits a hitter would get in 100 at-bats. Not surprisingly, the number of hits containing the highest probability for the respective groups are its true talent hit rate for 100 at-bats. In other words, we see 10 hits as being most probable in the T10 group and 25 hits as most probable in the T25 group.

Another observation you might make is that the T10 group has a tighter variance than the T25 group. This is a property of the binomial distribution, where variance is equal to $np \times (1-p)$. You can see that proportions that are closer to 0 or closer to 1, will have less variance than a proportion closer to the middle. (The Bernoulli distribution, which is just one trial of a binomial distribution, shows a similar property, something I wrote about in a previous post.)

Another way to think about solving the problem is to use the heights of the black and red lines at 18 hits, but weighted by what we know about the two groups of baseball hitters (our “priors”). If we were to use the graph above, the probability of getting 18 hits in 100 at-bats, given that they have a true talent level of 10% hit rate would be:

$\text{P}(\text{T10} | \text{18H}) = \frac{\text{height of black line at 18 hits} \times 0.6}{\text{height of black line at 18 hits} \times 0.6 + \text{height of red line at 18 hits} \times 0.4}$

Putting it all together

Let’s return to the parameters of the Bayes’ theorem equation and start bringing the pieces together.

${\text{P}(\text{18H})}$ = $\text{P}(\text{18H} | \text{T10})$ + $\text{P}(\text{18H} | \text{T25})$

We can apply the probability mass function starting first with the T10 group. (Note that we can ignore calculation of the binomial coefficient since this will cancel out in the final equation. I’ll use the term $\propto$ to represent “in proportion to.” in the equations below.)

$\text{P}(\text{18H} | \text{T10}) \propto (0.1^{18} \times 0.9^{82}) $

$\text{P}(\text{18H} | \text{T25}) \propto (0.25^{18} \times 0.75^{82}) $

We now have everything we need to plug into our equation.

$\text{P}(\text{T10} | \text{18H}) = \frac{\text{P}(\text{18H} | \text{T10})\text{P}(\text{T10})}{\text{P}(\text{18H})}$

$\text{P}(\text{T10} | \text{18H}) = \frac{(0.1^{18} \times 0.9^{82}) \times 0.6}{(0.1^{18} \times 0.9^{82}) \times 0.6 + (0.25^{18} \times 0.75^{82}) \times 0.4} $

After all that math, we have (drumroll) $\text{P}(\text{T10} | \text{18H}) = 0.243$.

Therefore, there is 24.3% probability that Aguila has a true talent level of a 10% hit rate.

There you have it! This application also applies the diachronic interpretation of Bayes’ theorem, which is a fancy way of saying that the hypothesis (whether Aguila is in the 10% true talent group) can be updated with time (after 100 plate appearances). (I found a nice explanation from Allen Downey’s book here.)